Preparing your PDF for download...

There was a problem with your download, please contact the server administrator.

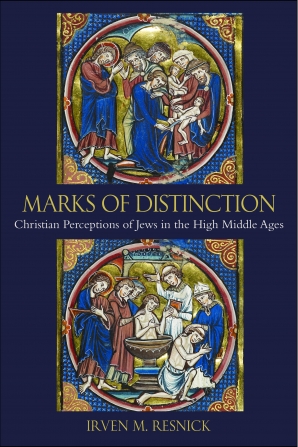

Marks of Distinction

Christian Perceptions of Jews in the High Middle Ages

Imprint: Catholic University of America Press

For medieval Latin Christendom, authoritative texts such as the Bible and the writings of the Fathers of the Church provided a skeleton that gave form to Christian perceptions of Jews and Judaism. Eye-witness testimony, hearsay, reports of converts from Judaism, and the testimony of dreams, visions, and miraculous events helped fill in the body with concrete detail. In this newest work, renowned author and scholar Irven Resnick explores the additional support drawn from medieval science. Resnick presents a captivating study of long-held medieval scientific theories that predisposed Jews to certain types of offensive behavior or even to communicate certain illnesses and disease. By arguing for a Jewish "nature" dictated by specific physical characteristics, medieval scientific authorities contributed to growing fears of a Jewish threat.

Through the use of several illustrations from illuminated manuscripts and other media, Resnick engages readers in a discussion of the later medieval notion of Jewish difference. Externally, these differences were evidenced by marks that physically distinguished Jews—and especially Jewish males—from their Christian neighbors, for example the mark of circumcision. Internally, their melancholy humoral complexion, further weakened by the Jews' dietary restrictions, was thought to dictate their temperament and sexual mores, and to incline them toward leprosy, bleeding hemorrhoids, and other infirmities. These differences were viewed by some as ineradicable, even following religious conversion; or, at best, erasable with only the greatest difficulty over several generations.

This work clarifies that the one doctrine of modern anti-Semitism typically thought to distinguish it so clearly from medieval anti-Judaism—the impossibility of escaping one's identity as a Jew even through religious conversion—had begun to appear by the end of the Middle Ages.

Irven M. Resnick is professor of philosophy and religion, and Chair of Excellence in Judaic Studies at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. He is a corresponding fellow at the Ingeborg Rennert Center for Jerusalem Studies at Bar-Ilan University and a senior associate at the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies. His most recent publications include translations of Albert the Great’s Questions concerning Aristotle’s "On Animals"; Petrus Alfonsi’s Dialogue Against the Jews; and Peter Damian’s Letters, all published in the Fathers of the Church Medieval Continuation Series by CUA Press.

"This is a book of generous profusion. It should be read not just by those interested in medieval Jews, but by all concerned to understand the fears that lead majorities to persecute minorities as an enemy within."

~Catholic Historical Review

"This is a learned and significant study… that will have a material impact on scholarly discourse regarding a topic of great significance."

~AJS Review

"Both medieval and modern historians long have debated the issue of the similarities and dissimilarities between anti-Semitism in the medieval and modern (especially post-1870) world… Now Resnick revisits this issue, very intelligently and with impressive erudition, showing that medieval beliefs--like the idea that Jewish men menstruated, that Jews gave off a special smell, and that Jews had a sallow, unhealthy complexion--had a more influential resonance in creating and sustaining the gulf between Jews and Christians in the Middle Ages than heretofore has been perceived. In sum, a very good book."

~Choice

" Marks of Distinction is a thought-provoking book offering an abundance of fascinating textual and visual sources. One of its most valuable features is that it presents the Christian concepts and interpretations of biblical laws and customs along with their Jewish counterparts."

~Zsófia Buda, Journal of Jewish Studies

"Irven Resnick enters into this debate with this thoroughly researched and fascinating study… Marks of Distinction offers a window into a wide array of medieval theories authors used to justify their contempt of Jews, lepers, and other outcasts, and this digs deep into the sometimes repulsive but endlessly fascinating underbelly of the medieval imagination."

~Frans van Liere, Calvin College

"Irven Resnick’s study offers an intriguing contribution to the history of Western Christian anti-Semitism… This book is a useful resource not only for medievalists, but also for a broader audience interested in the long history of anti-Semitism."

~Holocaust and Genocide Studies

"With palpable erudition, Irven Resnick has highlighted the extensive reflections by Christian thinkers in the high Middle Ages on Jewish physicality."

~Studies in Christian-Jewish Relations